Workshop on R

May 2018

Hosted by Virginia Education Science Training (VEST) Program at UVA

Overview Schedule Getting started Modules Data

Wrangling data II

R has undergone a transformation in the past few years and this may affect how you choose to approach data wrangling. While the core R functions for data manipulation are still the same, a new suite of packages, the tidyverse (formerly known as the “Hadleyverse” after their key creator, Hadley Wickham), has really changed the way many people use R.

In this module, I’m going to show you how to wrangle data the tidyverse way. The sequence is almost the same as those in the last module. In the end, it’s up to you which approach you prefer.

Data for this module are the same as those used in the last, from the NCES Education Longitudinal Study of 2002. For descriptions of the variables, see the codebook. If you saved your cleaned up data set using the same name, go ahead and download a fresh copy of the original data.

Tidyverse

The tidyverse is a shorthand for a number of packages that work well together and can be used in place of base R functions. A few of the tidyverse packages that you will often use are:

- dplyr for data manipulation

- tidyr for making data tidy

- readr for flat file I/O

- readxl for Excel file I/O

- haven for other file format I/O

- ggplot2 for making graphics

There are many others. A lot of R users find functions from these libraries to be more intuitive than base R functions. In some cases, tidyverse functions are faster than base R, which is an added benefit when working with large data sets.

Magrittr and pipes

The key feature of the tidyverse is its use of pipes, %>%, from the

magrittr package.

Pipes take output from the left side and pipe it to the input of the

right side. So sum(x) can be rewritten as x %>% sum: x outputs

itself and the pipe, %>%, makes it the input for sum().

This is a silly example (why would you do that?), but pipes are powerful because they can be chained together. Functions can be nested in R, but after too many, the code becomes difficult to parse since it has to be read from the inside out. Pipes allow functions to come one after another in the order of the work being done.

Let’s use Hadley’s canonical example to make the readability comparison between nested functions and piped functions clearer:

## foo_foo is an instance of a little bunny

foo_foo <- little_bunny()

## adventures in base R must be read from the middle up and backwards

bop_on(

scoop_up(

hop_through(foo_foo, forest),

field_mouse

),

head

)

## adventures w/ pipes start at the top and work down

foo_foo %>%

hop_through(forest) %>%

scoop_up(field_mouse) %>%

bop_on(head)

Data wrangling with tidyverse

## library

library(tidyverse)

── Attaching packages ────────────────────────────────── tidyverse 1.2.1 ──

✔ ggplot2 3.1.0 ✔ purrr 0.2.5

✔ tibble 1.4.2 ✔ dplyr 0.7.8

✔ tidyr 0.8.2 ✔ stringr 1.3.1

✔ readr 1.3.1 ✔ forcats 0.3.0

── Conflicts ───────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

Let’s reread the original data. Like read.table(), read_delim() is

the generic function that needs you to give it the separating/delimiting

character. You could also just use read_csv().

## read in the data

df <- read_delim('../data/els_plans.csv', delim = ',')

Parsed with column specification:

cols(

.default = col_double(),

psu = col_character(),

bysex = col_character(),

byrace = col_character(),

bypared = col_character(),

bymothed = col_character(),

byfathed = col_character(),

byincome = col_character(),

bystexp = col_character(),

f1psepln = col_character(),

f2ps1sec = col_character()

)

See spec(...) for full column specifications.

Unlike the base R read.table() function, read_delim() prints out

information about how the data were read in. Nothing is wrong! The

read_delim() function, like many other functions in the tidyverse,

assumes you’d rather have more rather than less information and so acts

accordingly.

We can see which columns were read in as doubles (col_double()) and

which as integers (col_integer()). If the column name isn’t in the

list, then it was read in as the .default, which was as a character

column (col_character()).

Mutate

To add variables and change existing ones, use the mutate() function.

Most if not all of the primary tidyverse functions take the data object

as the first argument. So the mutate() function would be mutate(df,

...) where ... is the stuff we want to do. Because we’re using the

%>%, however, we start with the data by itself and pipe it into the

mutate() function. We’ll do this with the rest of the tidyverse

functions. While not necessary, I think it helps reading through the

code: Starting with the data (df), we next create new variables with

the mutate() function… and so on.

Note that with tidyverse functions, you usually don’t need to use the

data frame name with the dollar sign construction (df$<var_name>) and

you don’t need to put quotation marks around the column names. There are

some rare cases where you do, but we won’t get into those.

## assign values inside function using = sign (not <-)

df <- df %>%

mutate(ones = 1,

avg_test = (bynels2r + bynels2m) / 2) # ignore neg vals

To conditionally mutate variables, use the ifelse() construction

inside the mutate() function.

## (1) make a numeric column that == 1 if bysex is female, 0 otherwise

## (2) assign DOB an NA if < 0

df <- df %>%

mutate(female = ifelse(bysex == 'female', 1, 0),

bydob_p = ifelse(bydob_p < 0, NA, bydob_p))

Quick exercise

Create dummy variables for each race/ethnicity category in

byrace. (Hint: use (table()) to see the possible values; adv. hint:ifelse()statements can be nested.)

Select

To choose variables, either when making a new data frame or dropping

them, use select(). Without assignment (because we would change our

data object and we don’t want to), let’s use select() to view the

first few rows of the student and school ids.

## just view first few rows of stu_id and sch_id (no assignment)

df %>% select(stu_id, sch_id)

# A tibble: 16,160 x 2

stu_id sch_id

<dbl> <dbl>

1 101101 1011

2 101102 1011

3 101104 1011

4 101105 1011

5 101106 1011

6 101107 1011

7 101108 1011

8 101109 1011

9 101110 1011

10 101111 1011

# ... with 16,150 more rows

To drop variables, use a negative sign (-) in front of the variable

name. This time, we will reassign the results to df, which means that

the column f1pnlwt will be dropped from the data frame.

## drop follow up one panel weight

df <- df %>% select(-f1pnlwt)

## check names

names(df)

[1] "stu_id" "sch_id" "strat_id" "psu" "f1sch_id" "bystuwt"

[7] "bysex" "byrace" "bydob_p" "bypared" "bymothed" "byfathed"

[13] "byincome" "byses1" "byses2" "bystexp" "bynels2m" "bynels2r"

[19] "f1qwt" "f1psepln" "f2ps1sec" "ones" "avg_test" "female"

Quick exercise

Without assigning back to your data frame (no

<-), see if you can first keep a set of variables and then drop a set of variables. (Hint: considerc())

Filter

Like select() works on columns, filter() can be used to subset based

on row conditions. Earlier we properly labeled bydob_p values less

than zero as NA. Let’s drop those.

## show number of rows

nrow(df)

[1] 16160

## keep if not (!) missing

df <- df %>% filter(!is.na(bydob_p))

nrow(df)

[1] 15183

Quick exercise

Filter out observations if they are missing

bysexvalues. You can do it in two steps, firstmutate()ing negative values to beNAand thenfilter()ing out missing values, or in one step, justfilter()ing out ifbysexhas a value below zero.

Arrange

Sort values using the arrange()

function.

## show first few rows of student and base year math scores (tidyverse way)

df %>% select(stu_id, bydob_p) %>% head(10)

# A tibble: 10 x 2

stu_id bydob_p

<dbl> <dbl>

1 101101 198512

2 101102 198605

3 101104 198601

4 101105 198607

5 101106 198511

6 101107 198510

7 101108 198607

8 101109 198512

9 101110 198505

10 101111 198507

## arrange

df <- df %>% arrange(bydob_p)

## show again first few rows of ID and DOB

df %>% select(stu_id, bydob_p) %>% head(10)

# A tibble: 10 x 2

stu_id bydob_p

<dbl> <dbl>

1 133211 198300

2 195210 198300

3 195213 198300

4 225203 198300

5 268219 198300

6 268225 198300

7 274222 198300

8 280215 198300

9 324119 198300

10 327128 198300

Quick exercise

arrange()bybydob_pagain, but this time in reverse order. Google “dplyr arrange” to find information about the function and see if can figure out how to sort in descending order.

Summarize

Aggregate data using the summarise() or summarize() function

(they’re the same, just playing nice by offering both spellings).

Unlike the aggregate() function, you first need to set the grouping

variable using the group_by() function. Since we need to replace

negative values before we summarize, we’ll chain a few functions

together into one command.

Notice how we can include comment rows between each piped command. Adding a comment before each function that explains the step in a human-friendly manner can be particularly helpful when chaining multiple functions together. Or you can work the other way, writing pseudocode first and then adding the R code afterwards.

## create new data frame

sch_m <- df %>%

## (1) make test score values < 0 into NAs

mutate(bynels2m = ifelse(bynels2m < 0, NA, bynels2m)) %>%

## (2) group by school ID

group_by(sch_id) %>%

## (3) get the average math score, removing missing values

summarise(sch_bynels2m = mean(bynels2m, na.rm = TRUE))

## show

sch_m

# A tibble: 751 x 2

sch_id sch_bynels2m

<dbl> <dbl>

1 1011 45.3

2 1012 43.3

3 1021 28.9

4 1022 38.6

5 1031 40.0

6 1032 35.3

7 1033 42.2

8 1041 44.9

9 1042 52.2

10 1051 45.9

# ... with 741 more rows

Quick exercise

Find the average reading test score for each school and save it in an object.

The group_by() and summarise() functions are very useful for

generating summary statistics and exploring your data. We’ll use them

more in the modules on exploratory data analysis.

Join

Rather than saying “merge,” dplyr uses the SQL language of joins:

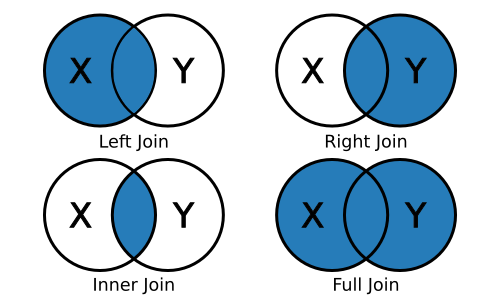

left_join(x, y): keep all x, drop unmatched yright_join(x, y): keep all y, drop unmatched xinner_join(x, y): keep only matchingfull_join(x, y): keep everything

Since we want to join a smaller aggregated data frame to the original

data frame, we’ll use a left_join(). The join functions will try to

guess the joining variable (and tell you what it picked) if you don’t

supply one, but we’ll specify one to be clear.

## join on school ID variable

df <- df %>% left_join(sch_m, by = 'sch_id')

Quick exercise

Join the average reading test score data frame you made to the main data object.

Write

The readr library can also write delimited flat files. Instead of

write_delim(), we’ll use the wrapper function write_csv() to save a

csv file. Again, it’s a good habit to save any modified data using a

different name so that your raw data stays untouched. We’ll add

_mod_tv to the data name so that we don’t overwrite raw data or the

modified data set we made in the last module.

## write flat file

write_csv(df, '../data/els_plans_mod_tv.csv')